Commentary: Data centers and their neighbors

Published 6:54 am Thursday, June 12, 2025

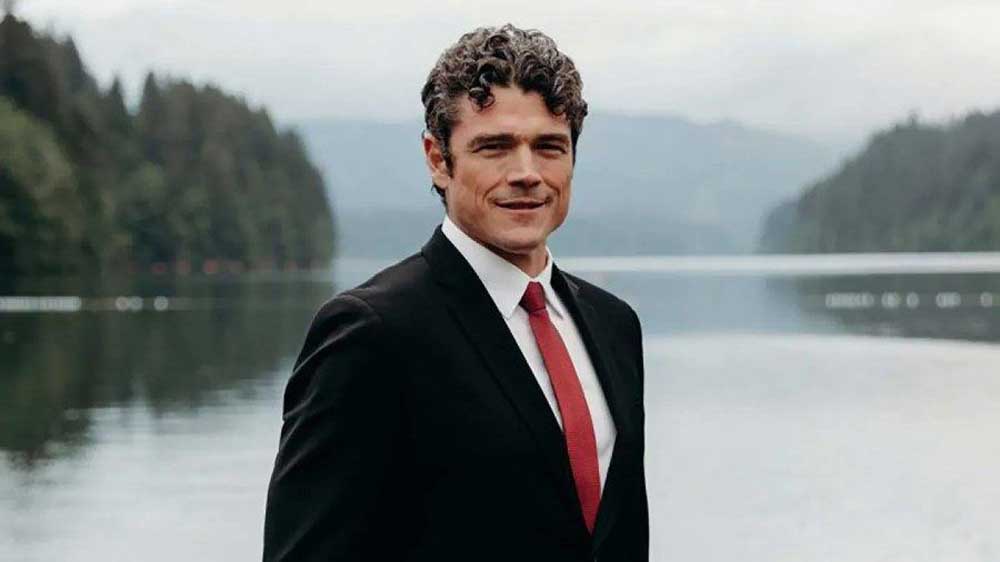

- Data centers in Umatilla and Morrow counties are expanding their presence in terms of economic impact. These centers, county leaders say, offer a significant and stable tax base. (Amazon Web Services/Contributed Photo)

Randy Stapilus has researched and written about Northwest politics and issues since 1976 for a long list of newspapers and other publications. A former newspaper reporter and editor, and more recently an author and book publisher, he lives in Carlton.

Oregon has a big and (relatively) new kind of business it doesn’t really know how to deal with. It should start soon to figure that out.

This new sector consists of its mass of data centers, more of which are likely to pop up in coming years. But the state has no overall strategy for dealing with them.

It should, because data centers, economically significant and technically important as they are, are a business unlike any other. Governments need a separate and specific set of policies to deal with them.

Trending

One reason the state (like many others) has been behind the curve may be inadequate information about the sector, but more is becoming available.

Organizations that track data centers aren’t in agreement about exactly how many the state has: 131 according to Data Center Map, 84 according to datacenters.com. The timing of their surveys could have affected the difference in numbers, but so could questions about how you count them.

Data Center Map, for example, says that the largest grouping of centers in the state is at Boardman, with 30 centers listed. All, however, are Amazon AWX PDX, bunched in five different campuses. How many distinct units of these should be counted comes down to a matter of definition.

Regardless of the exact numbers, Oregon clearly is among the state leaders for data centers. It has fewer than California and about the same as Arizona, but more than any other state west of Texas. About 2,500 data centers are estimated to exist in the United States, so Oregon’s share is above average per capita.

One attraction for the state is cheap hydropower: Most of the centers are located not far from the Columbia River. Oregon’s moderate climate and relative safety from natural and human-caused disasters are pluses as well.

For some purposes, data centers are classified as large industrial operations, which they are — but they’re also distinctive from most businesses in that category. They not only use unusually large amounts of electricity but water as well, and they employ far fewer people than most industrial businesses usually do.

Trending

The tracking site datacenters.com said “Oregon, with its strategic geographical location, offers several advantages that make it an ideal choice for businesses looking to store their data. The state boasts a robust technology infrastructure, including reliable power supply and high-speed internet connectivity. Additionally, Oregon’s temperate climate ensures optimal cooling conditions for data centers, reducing energy consumption and associated costs. These factors contribute to the overall efficiency and reliability of the colocation services available in the region.”

Several private data companies dominate the service provision in Oregon: Lumen Colocation appears to be the largest. But Google has a large center in The Dalles, Amazon in Boardman, Hermiston and Umatilla, and both Meta (Facebook) and Apple have substantial operations in Prineville.

Besides those well-known locations, Oregon has data centers in Portland, Eugene, Medford, Bend, Hillsboro, Corvallis, Baker City and Bandon. It’s truly an industry with statewide reach.

They are significant economic players, but they have been walled off from much of the rest of the state’s economic and social picture in ways most businesses are not. Their impact on the state and on their neighbors in the areas of electric power, water use, and much more may become large, and it’s not entirely predictable. How should we interact with them? What should we fairly expect of them? That’s a broad debate begging for a legislative airing.

The Oregon Citizens Utility Board, a consumer-oriented nonprofit, said that “utility investments to serve data centers have been pushing up billing rates to residential, small business, and even other industrial customers. We’ve seen the dire impact of data centers’ rapidly rising energy costs — in 2024, Oregon’s for-profit utilities disconnected a record number of households because they could not afford their electricity bills.”

The Oregon Legislature has taken note of this specific issue..

This year’s House Bill 3546, sponsored by Reps. Pam Marsh, Mark Owens, and Dacia Grayber and Sens. Janeen Sollman and Jeff Golden, covers a narrow though significant segment of data center impact: Electric power rates. It passed the Senate on June 3 and the House cleared amendments from the other chamber on June 5, in both cases with generally Democratic support and Republican opposition. The bill goes to the governor next for final action.

That bill raises sensible questions, but it should be the foot in the door to a broader discussion of how these centers should relate to the rest of us.

Data centers should be put in a new category by themselves, for utility, regulatory and service purposes. Working through that effort should be a long-term project starting now.